EPICENTRO | COVID-19

Alzano L.do – Nembro

Portraits and emotions

2020

Book published 2021

“Epicentro” is a tool-book for understanding, each other and oneself first and foremost. It recounts the coronavirus experience in Alzano L.do and Nembro from an emotional and psychological perspective.

Epicentro is available in Italian.

You can order an autographed

copy sending an e-mail

Maurizio Milesi lives just a few hundred meters from Alzano Lombardo, a small town in Bergamo that, until a few months ago, had never had access to international news, except for reference to some large industrial plants located there. A similar argument applies to the town of Nembro, which borders Alzano Lombardo.

It is precisely work in industry that is one of the constituent factors of the individual and collective identities of these towns as, more generally, those of the entire Seriana Valley. These are areas where, after World War II, there has (almost) never been a lack of work, the majority of the population enjoys high standards of well-being, and many citizens feel that they are part of the most advanced tip of the Italian system, that they represent its productive heart, its backbone.

Widespread, too, is the belief that it has a state-of-the-art health care system that lives up to its status as an economically developed country. And, certainly, in Lombardy the healthcare is there and people are being treated. But then came 2020 and with it the Coronavirus pandemic to draw a periodizing line in the history of these communities.

Henceforth, there will always be a before and an after those months of March and April 2020 when Alzano Lombardo and Nembro became, together with their inhabitants, the subject of international attention because, for reasons partly coincidental and partly related to their socio-economic structure, they became the epicenter of the pandemic in Italy.

And, while the world press told of the dozens of deaths daily counted in the Seriana Valley and questioned the reasons why the “Pesenti Fenaroli” Hospital had become a place of great spread of the virus, the local population was experiencing collective vulnerability for the first time since the postwar period. They were becoming aware of their own fragilities and the limitations of their economic, social, and health systems.

Locked in their homes and besieged by constant siren sounds, the citizens of Alzano Lombardo and Nembro were forced to deal with an out-of-control increase in mortality, made evident even by the abnormal display of funeral vestments at the gates of their homes. Death and disease put the area under siege, making any effort to remove the pandemic from the mental horizon impossible.

To the fear of contagion, death and disease was added in many the fear of losing their economic solidity. Uncertainty was rampant, the future took on gloomy hues in the eyes of many, filling with question marks. After a couple of months from the start of the epidemic, the death toll confronted the reality of a decimated generation: those over 60 died, in those two months, in unprecedented percentages, and many of them felt only then, for the first time, truly elderly.

The younger generation, on the other hand, lived in the anxiety of infecting their fathers and mothers, having to endure the necessity of confinement to the private family just during that age when one must and wants to do exactly the opposite, which is to go out, meet people, be with friends, love. The lost generation left an important void on many levels: those elders, in fact, were often active in the economic and social life of their villages, were animators of associations, as well as historical memories of the community, fathers, mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers.

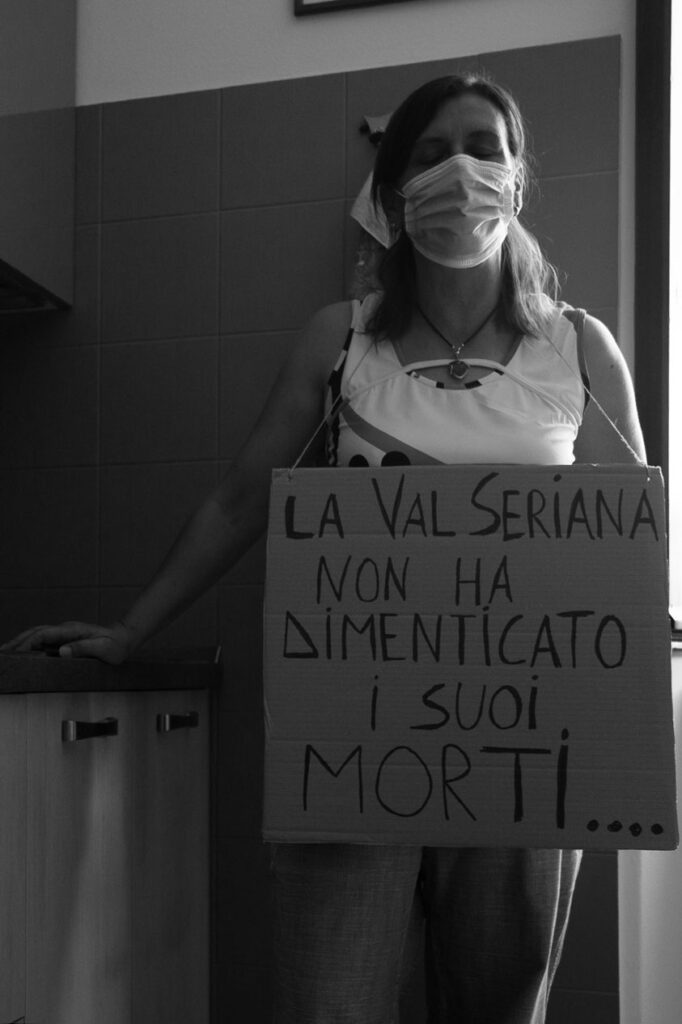

With their disappearance, the need to deal with the collective dimension of mourning has opened up, the need for processing work has imposed itself, because that tragedy did not only affect individuals who had to bear the departure of a relative, but it took on the dimension of a collective, communal fact.

It became important to resist the temptation of removal, to make memory, to rethink what happened in order to

take it back in hand, in an effort to tame the ghosts it has generated.

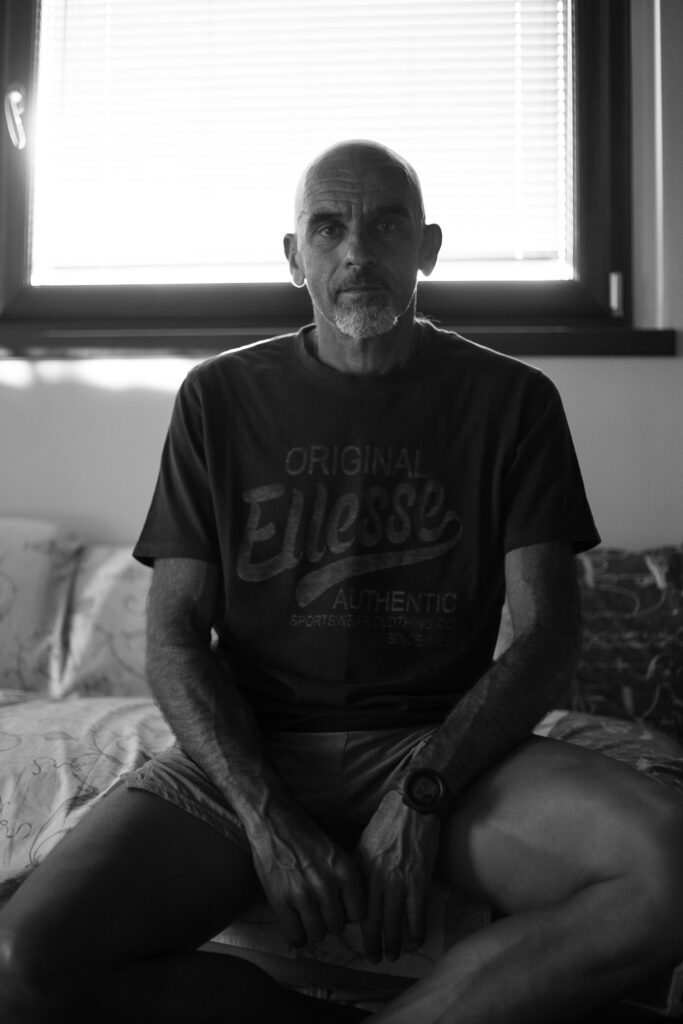

The work of photographer Maurizio Milesi finds meaning precisely from this perspective. It is the work of a “survivor” who seeks to dialogue with other “survivors,” to constitute a local archive of memory.

There are pictures and words, there are the faces of some witnesses and their first-person accounts. There are the experiences and

subjective experiences, put down on paper to allow themselves to name the tragedy that has been unleashed-and that is reappearing on the scene in the hours in which I write these lines, mainly in other places, in the form of a second wave. But, together, these photos and stories are a product for the benefit of the community, which will also enable generations today who are children to return tomorrow to that pandemic that has

taken away from them, abruptly and suddenly, the hugs, the care, the cuddles, the love of their grandfathers and grandmothers. Maurizio Milesi’s, in short, is a useful piece in the process of processing the catastrophe we have experienced.

Paolo Barcella

Bergamo, 28/10/2020

Epicentro is available in Italian.

You can order an autographed

copy sending an e-mail

€ 14